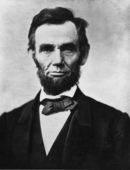

Abraham Lincoln has been elevated almost to the status of a political deity in American history, a deity who “preserved the Union” and “freed the slaves.” He was a remarkable man born in 1809 to a poor family living in a one-room log cabin in Kentucky. His parents moved the family to Indiana and then Illinois so that they could live in a “free” State and escape from the disease-plagued Kentucky. Astute, strong, tall (1.93 m), and hard-working, Lincoln was an avid reader and self-educated. He earned a living splitting wood, then invested in a general store before entering politics and the legal profession. Although he lost many of his early election campaigns, he persevered and was elected to the Illinois State House of Representatives. In 1846, he was elected to one term in the U.S. House of Representatives; but he lost his campaign for the U.S. Senate in 1858, where he famously declared that “A House divided against itself cannot stand.” In May 1860, Lincoln astutely pursued and succeeded in obtaining the Republican Party nomination for President; and in the general election later that same year, he won – just barely. The country was sharply divided on the issues of slavery, protective tariffs, and centralized government when Lincoln took office in March 1861.

Lincoln was devoted to the principles of the “American System.” Its three leading tenets were:

- protectionism;

- “internal improvements” (government-subsidized canal and railway development, and other related interventionist policies);

- and a national banking system.

Lincoln’s speeches and letters show that Lincoln’s entire domestic policy agenda was focused on advancing these three goals. The Northern and New England States were the U.S.’s manufacturing center. Here, the commercial interests lobbied for high tariffs and other trade barriers to keep out less-expensive and better-quality European industrial goods. The South, on the other hand, was the main exporting region of the USA, specializing in cotton, tobacco, and other goods, and it imported most of its finished goods. So, the South opposed high tariffs and trade barriers, while the Northern States and Lincoln supported a system of high tariffs. Yet, the South’s ports collected 75% of all Federal tax revenue. Without that, the Federal government would starve.

Lincoln also advocated major public works by the Federal government. The greatest resistance to this also came from the Southern states in Congress. Finally, Lincoln wanted a national central banking system to supply cheap credit and loans both to fund these government “internal improvements” and for businesses. Historically, most Southern States resisted a centralized banking system as a threat to their economic interests and well-being. Those were the real, leading factors behind Southern secession from the Union. When Lincoln entered the White House in March 1861, many in the South believed that he would greatly push for greatly increased Federal government spending and control.

Slavery was a side issue, and even Lincoln – an opponent of slavery – declared “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it. If I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would also do that. What I do about slavery and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save this Union.” Lincoln was a masterful politician, bringing together—and holding together—all of the main factions of his Republican Party, and bringing in War Democrats; but he could not allow the Federal government to lose most of its tax revenues.

Slavery was a side issue, and even Lincoln – an opponent of slavery – declared “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it. If I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would also do that. What I do about slavery and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save this Union.” Lincoln was a masterful politician, bringing together—and holding together—all of the main factions of his Republican Party, and bringing in War Democrats; but he could not allow the Federal government to lose most of its tax revenues.

The “War Between the States” began in April 1861; and Lincoln presided over the North during this American Civil War (1861-1865), in which the North and the South fought each other bitterly. Government power grew greatly during the War, and the South was defeated. 620,000 lives were lost. As for the slavery issue, Lincoln saw that freeing the slaves was merely a pragmatic political tool that he decided to use when the war was going badly for the Union side. His Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 freed slaves, but only in those areas of the South still under Confederate control and not elsewhere in the United States. While opposed philosophically to slavery, Lincoln had long argued that it was constitutionally legal and could not be overthrown without a constitutional change or by the states themselves. He did not believe in the equality of blacks and whites, thinking that blacks were inferior to the white population in general. He opposed integration and intermarriage, did not think that freed slaves should be given full legal and voting rights equal to whites, and forcefully advocated before and during the Civil War that all blacks should be deported by government subsidy either back to Africa or to the West Indies.

In addition, thousands of opponents of Lincoln’s war policies were arrested and imprisoned for the duration of the Civil War. The writ of habeas corpus was revoked, and mail and press censorship was imposed. Taxes were dramatically increased and a national banking system was established that made the new paper money, “greenbacks,” legal tender, resulting in the worst inflation in U.S. history since the American Revolution. Lincoln was not popular during his first term, but was re-elected by a landslide in 1864 for his second term. And he was immortalized after his assassination in April 1865. Yet, Lincoln and the Civil War pushed policies that were the beginning of centralized and intrusive government in America. His policies represented the beginning of the end for the idea of limited government expressed by the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

Yet, as the recent Spielberg film has shown even with its historical inaccuracies, Abraham Lincoln was a skilled political leader who ultimately succeeded in his goals.

Vous avez participé à une session ?

Vous avez participé à une session ?